Linux OS Jitter

09 Jul 2017Exploratory Study on the Linux OS Jitter - Vicente, et al. 2012

At work, we have been looking into problems related to OS jitter. The same benchmark, run on the same machine, with the same data issueing different results on different runs. Would it be a Java application, I would have had a tendency to quickly attribute it to JVM hiccups, but the application under test was written in C++. So, I started to look for papers on OS Jitter and will be commenting out an interesting one here.

In this paper, we present the results of an experimental study that quantifies the effects of different sources of OS Jitter in the Linux operating system. We use the design of experiments (DOE) method to conduct controlled experiments statistically planned.

The results are interesting and the statistical rigor applied as well. The paper has two main contributions, first to show that processor topology, and especially shared processor caches, have a major role on OS Jitter. Second that, for distributed workloads, the number of computational phases in the algorithm has a quite more important influence than the number of distributed compute nodes.

HPC cluster-based applications are typically designed to run in a paradigm of parallel processing, where instructions are programmed to be executed in many computational phases [2]. In this approach, after all distributed processes finish a given computational phase they all synchronize and then start executing the subsequent phase [4]-[6]. Since a new phase only starts after all distributed processes conclude the current phase, synchronizing the computing time of all application processes is critical. The last process that terminates a given phase determines the time length of the phase. So, reducing the runtime variability in each node is a major requirement, given that the occurrence of unexpected delays in a node will spread along other nodes involved in the same computational phase, bringing a longer time to complete the whole task.

From previous work (Kothari et al. 2007) mentioned in the paper, the main source of jitter was the timer interrupt (63%) and the rest was attributed to come from different OS daemons and other hardware interrupts. The Linux kernel has implemented what is called tickless kernel on version 3.10. As a side note, it seems that it was already available on Solaris since 1999.

The first actionable advice for reducing external influences that we can take from the paper is turning off Linux automatic CPU frequency regulation.

This is done by recompiling the Linux kernel with the option “CPU Frequency Scaling” (CONFIG_CPU_FREQ) turned off. This feature allows the Linux kernel to change dynamically the processor frequency, affecting the run time length of the application processes.

Three experiments are described in the paper. In all experiments, the test application is running on a single CPU.

The Experiment #1 plays with five factors, which are turned on and off, called levels (+) and (-) in the paper:

-

Runlevel: Defines the OS services loaded during the system initialization. Runlevel 5 means a higher number of services loaded. This is typically the default level for many Linux distributions. Runlevel 1 has a minimum set of services loaded;

-

Kernel timers: Used to allow the execution of kernel and user level routines at a given future time;

-

IRQ: Hardware interrupts. On level (+) all IRQs are handled by the same processor handling the application. On level (-) no IRQ is handled by it. This is achieved using Linux “SMP IRQ affinity”;

-

Processor affinity: With this option set (+), no other system process will run on the same CPU where the test application running. All system processes are actually set to run on a specific processor. With the option unset (-), system processes can run on the same CPU where the application is running;

-

Timer interrupt: Finally, the timer interrupt is the last factor to be enabled/disabled in this experiment.

Each configuration set is called a “treatment” in the article, and each treatment is run 53 times. Overall, we have 2^n configurations possible, where n is the number of factors used in the experiment. Thus, for experiment #1 we have 32 treatments to run.

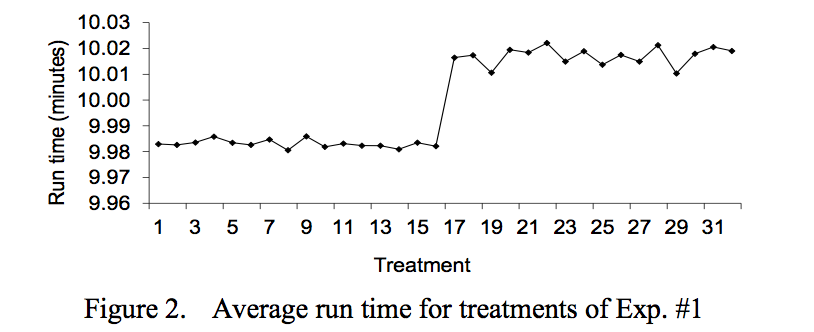

Looking at the results of Experiment #1, we can clearly see that the first 16 treatements don’t show much variability and there’s an extra factor, turned on starting on treatement 17, that raises the average runtime and increases the runtime variation. It’s the timer interrupt.

We found that 91.23% of the test application run time variation is caused by factor E (timer interrupt).

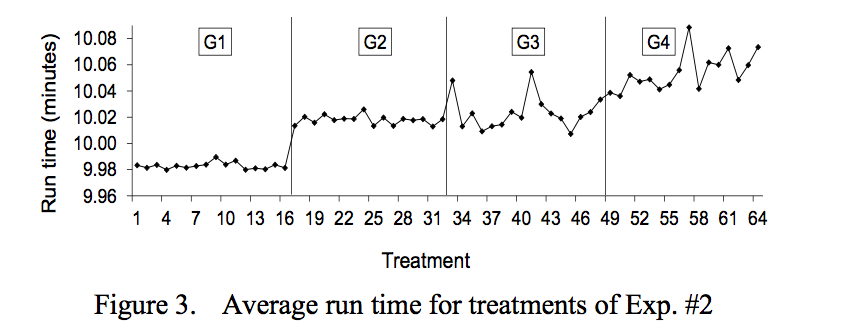

Experiment #2 adds a CPU-intensive process running on another CPU sharing Level-3 cache with the application already used on Experiment #1. This extra factor doubles the number of treatments needed for this experiment, when compared to experiment #1, taking it to a total of 64 treatments.

We consider the influence of cache as a source of OS Jitter because the operating systems manages the memory cache in various ways (e.g. cache aware scheduling).

To ease the analysis, the results are divided in 4 groups (G1 to G4). G1 and 2 change the same factors of Experiment #1, so there’s nothing new. On the G3, the timer interrupt is disabled, but the new factor of this experiement, which the second CPU-intensive process sharing the L3-level cache is enabled (factor F). We can see that the influence of this new factor in the run time variability is very similar to the one of the timer interrupt. On G4, both factors E and F are enabled and the increase in average run time and variability is clearly seen.

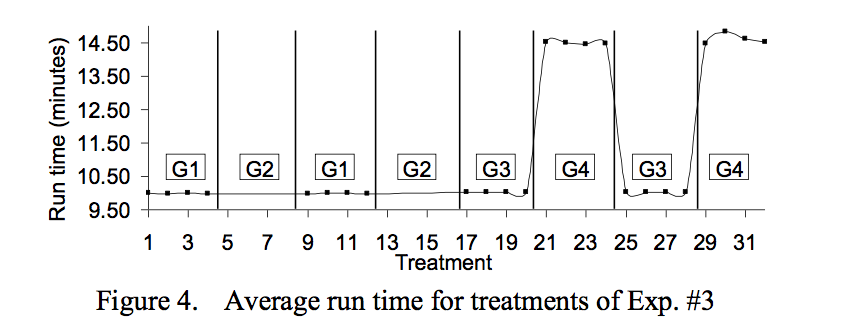

Experiment #3 introduces a network-related task to observe the interference of network interrupts on the test application. It runs on another processor (PU #2), but on the same socket, of the application we’re using to test the runtime. This experiment does not disable IRQ and timer interrupt, when the network-related task is enabled, because doing so makes the kernel routines responsible for the datagram packet processing work improperly.

G4 is the group where both we have the new network-related task running on PU #2 and the hardware interrupt and timer interrupt enabled on the PU #1 (the one running the application). We can see that it has a bigger impact on average run time than the worst case of the sharing cache case, in experiment #2.

So far, a single node application has been studied, but the paper goes on the analyze the impact of OS jitter on an application running on multiple nodes and composed of several computational phases. It then concludes that

in order to reduce the effects of OS Jitter on the runtime of distributed applications, it is a major requirement to reduce the number of computational phases per processes, even though it would require a significant increase on the number of processes (or compute nodes).

It’s good to keep in mind that computation phases here need refer to steps in an HPC application, where at the end of each step all processes need to synchronize (i.e. rendez-vous).

Conclusion

My main interest on this paper was on the first part, where it look into OS Jitter itself and we can basically draw the following rules-of-thumb:

- Turn off Linux automatic CPU frequency regulation;

- Use a tickless kernel (see limitation in the link mentioned above);

- Avoid running another CPU intensive process sharing the L3-level cache, even if the two processes are set to run on separate processors;

- Network jobs and the associated interrupts can have a worse impact than L3-level cache sharing.

I hope to be able to share the results of some experiments with these settings in a future post.